Time-Ins vs Time-Outs: Why Connection Works Better Than Isolation for Kids

What’s inside this article: A comprehensive guide to time ins versus time outs, information about why kids ‘misbehave,’ the neuroscience behind why connection works better than isolation, and step-by-step time-in implementation strategies for every age group. Plus, answers to some common parent concerns and specific tips for neurodivergent children.

Picture this.

Your three-year-old is playing with blocks when you say it’s time to get ready for bed. “NOOOOO!” they scream, throwing themselves dramatically on the floor.

Your instinct might be to send them to time-out because they need to learn a lesson, but what if there was a better way?

Time-outs are an age-old discipline strategy used by parents. It’s been around for generations, and it’s the go-to choice for many parents when their young kids aren’t listening.

Time-ins, on the other hand, are a newer concept, and they’re changing how parents handle challenging behavior by focusing on connection instead of isolation.

Rather than sending children away to “think about what they did,” time-ins bring you closer together during challenging moments.

This approach isn’t just gentler-it’s backed by decades of research on brain development, attachment theory, and emotional regulation. When you understand why your child’s brain works the way it does, everything changes.

This article will take a more comprehensive look at time-ins versus time-outs, what time-ins really are, the research behind them, and how to use them successfully.

Time-In vs Time-Out

You might be wondering what the difference is between the two. Is it just a different word for the same thing? How does one technique really differ from the other?

It’s important to really understand the difference in implementation so you can apply time-ins effectively.

What Are Time-Outs?

You probably already know this. But, time-out involves removing your child from a situation when they misbehave. Typically, they’re moved to a corner or a chair or another room, where they must sit quietly for a predetermined period of time (one minute per year of age is a common one).

Some parents require their child to face the wall or even place their forehead against the wall during their time out, while other parents have an “area” for time out or send them to their bedroom.

However, regardless of how you implement time-out, the theme is the same… during a time-out, your child is isolated from the activity and the environment where the ‘bad behavior’ occurred and usually doesn’t receive any attention from their parent or caregiver until the time-out is over.

The goal of a time-out is to punish your child for their poor behavior through isolation in order to stop them from behaving that way now and in the future.

What Are Time-Ins?

Time-ins are a positive discipline strategy that involves guiding your child to a safe space where you stay together and use co-regulation strategies and emotion coaching during moments of dysregulation. This helps children develop emotional intelligence and learn important skills, like how to calm their bodies, process their emotions, share their feelings, and even self-advocate more effectively.

Time-ins make children feel safe and connected rather than isolated. This helps kids build problem-solving skills and learn from their mistakes. Over time, children learn to respond thoughtfully rather than react impulsively.

Basically, instead of punishing a child for a behavior that is happening because they haven’t yet learned all the necessary skills required to even know what to do differently, you can use time-ins first to co-regulate and then teach those skills so they can navigate challenging and uncomfortable situations with success.

The core principles of time-ins include:

- Staying connected during difficult moments

- Teaching emotional regulation skills through co-regulation

- Addressing the underlying need behind the behavior

- Building emotional intelligence and self-awareness

- Maintaining the parent-child relationship during discipline

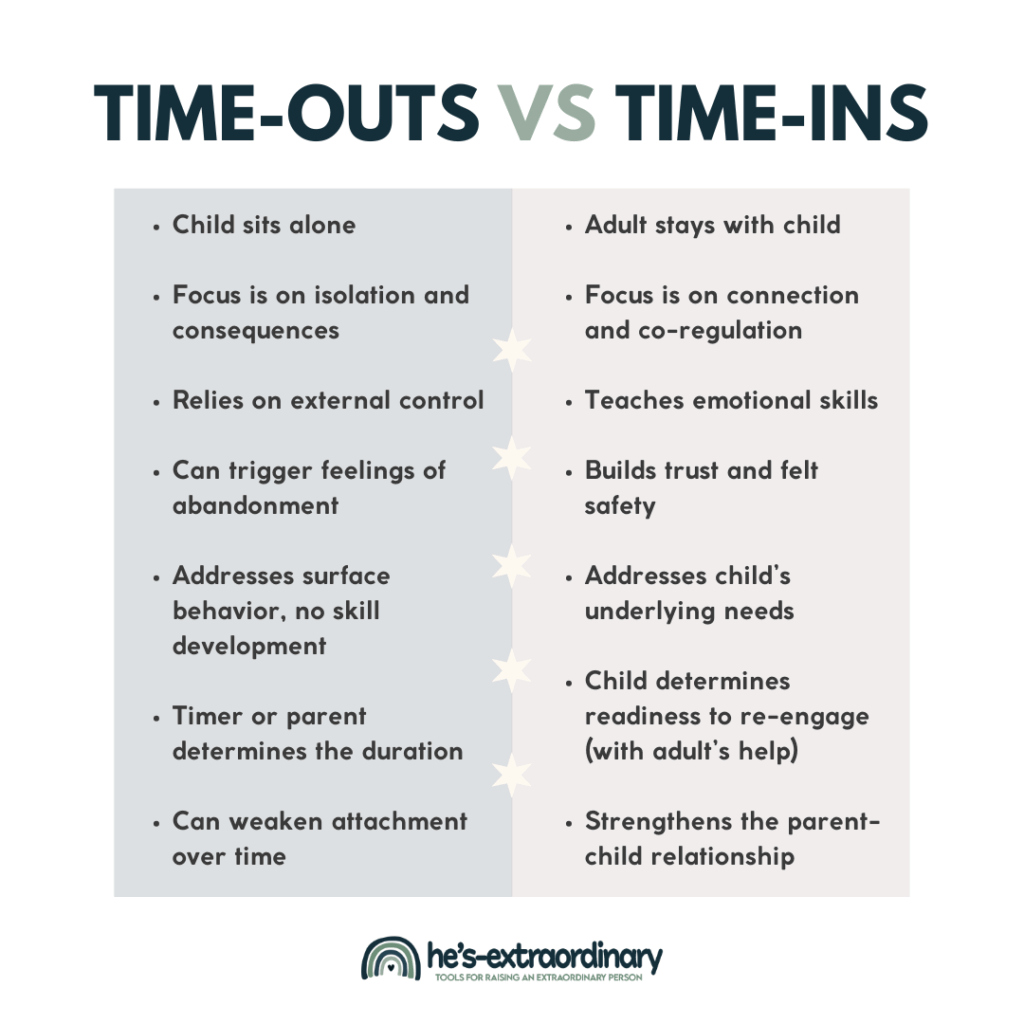

A Side-by-Side Comparison of Time-Outs and Time-Ins

Time-Ins:

- Adult stays with child

- Focus is on connection and co-regulation

- Teaches emotional skills

- Builds trust and felt safety

- Addresses child’s underlying needs

- Child determines readiness to re-engage (with adult’s help)

- Strengthens the parent-child relationship

Time Outs:

- Child sits alone

- Focus is on isolation and consequences

- Relies on external control

- Can trigger feelings of abandonment

- Addresses the surface behavior only, no skill development

- Timer or parent determines duration

- Can weaken attachment over time

The Science Behind Time-Ins

You might be wondering, “Well, who decided this is the better way and why?”

The research supporting time-ins comes from multiple fields of study, all pointing to the same conclusion: children’s brains need connection, not isolation, to develop healthy emotional regulation.

Brain Development Research

Here’s what every parent needs to understand about their child’s developing brain.

Dr. Daniel Siegel‘s research on childhood brain development shows us that the prefrontal cortex (the thinking brain responsible for logic, reasoning, and emotional regulation) isn’t fully developed until the mid-twenties (or later!).

This means young children literally cannot “think about what they did” while sitting alone in a time-out in the way adults often expect. Their brain simply doesn’t have the capacity yet.

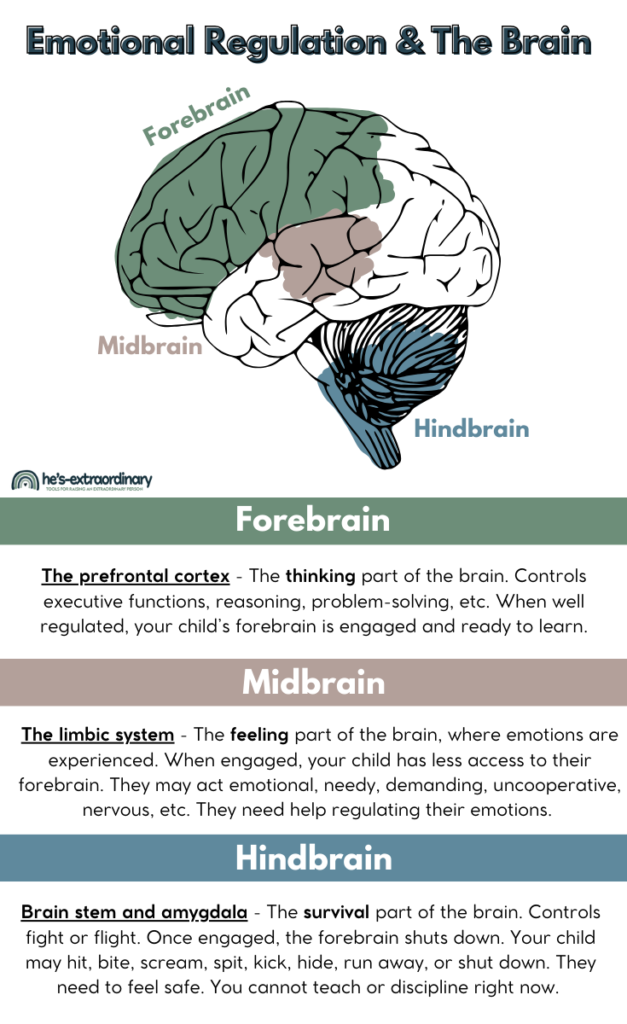

Think of your child’s brain like a three-story house:

- The Top Floor (Forebrain – The Thinking Brain): This is where logical thinking, problem-solving, and self-control happen. When your child is calm and feels safe, this part of their brain is “online” and ready to learn. This is when they can follow directions, make good choices, and actually think about their behavior.

- The Middle Floor (Midbrain – The Feeling Brain): This is where big emotions live. When your child gets upset, frustrated, or overwhelmed, this part of their brain takes over. They might whine, cry, cling to you, or act demanding. They’re not being manipulative – their feeling brain is just louder than their thinking brain right now.

- The Bottom Floor (Hindbrain – The Survival Brain): This is the most primitive part of the brain that’s focused on keeping your child safe. When this part activates, your child goes into fight, flight, or freeze mode. They might hit, scream, run away, or completely shut down. When the survival brain is in charge, the thinking brain goes completely offline.

The graphic above shows you exactly what’s happening in your child’s brain during these different emotional states. You can see how the three parts work together and why trying to reason with a dysregulated child just doesn’t work.

When kids are dysregulated, their midbrain or hindbrain (the emotional, reactive part, or survival brain) is in control. They need co-regulation from a calm adult to help them access the higher brain functions necessary for learning and reflection.

This is why time-outs often backfire. When you send a dysregulated child to sit alone, you’re asking their thinking brain to work when it’s completely offline. Instead of learning, they’re just sitting there with their survival brain activated, feeling scared and abandoned.

Time-ins work because they help calm the survival and feeling parts of the brain first so the thinking brain can come back online and actually learn from the experience.

Attachment Theory and Connection

Here’s what most parents don’t realize about how children are wired to connect.

Dr. Gordon Neufeld, a leading expert on child development, explains that kids are born “hardwired for attachment and belonging.” This isn’t just a nice idea – it’s a biological reality. Your child’s survival depends on staying connected to you, their primary caregiver.

When we use isolation as discipline, we activate their deepest fear – separation from their caregiver. From your child’s perspective, being sent away feels like a threat to their very survival.

This alarm response moves children into a state of caution and compliance, which is why time-outs might appear to “work” in the short term. But at what cost?

Here’s what’s really happening that most parents miss.

What “Caution and Compliance” Actually Looks Like

So, you send your child to time-out due to some form of unwanted behavior. When the time-out is over, your child returns, and the behavior has stopped.

You might be thinking, “Great! It worked!” and so you believe time-outs are an effective discipline strategy.

But what you’re seeing isn’t genuine learning or cooperation. It’s fear-based compliance.

Your child isn’t thinking, “Oh, I understand why that behavior was wrong, and I’ll make a better choice next time.” They’re thinking, “I better not do that again, or Mom/Dad might leave me.”

This compliance looks like:

- Immediately stopping the behavior when threatened with time-out again

- Walking quietly to time-out without arguing (after it’s been used repeatedly)

- Seeming “sorry” but repeating the same behavior later

- Being “good” right after time-out but having meltdowns about other things

- Appearing withdrawn or overly people-pleasing

However, this compliance comes at the cost of the attachment relationship. When children learn that love and connection are conditional on their behavior, it damages their sense of security and trust.

Why This “Success” Is Actually Harmful

Many parents resist moving away from time-outs because they see immediate behavior change. “But it works!” they say. And they’re right… kind of.

It often does work to stop behavior in the moment. The problem is what else it’s doing. When kids comply out of fear rather than understanding, several concerning things happen:

- They stop trusting you with their big emotions. Instead of coming to you when they’re upset, they learn to hide their feelings to avoid punishment.

- They become people-pleasers. They learn that love and acceptance depend on their behavior, not on who they are as a person.

- They develop anxiety. The constant threat of separation creates chronic stress in their developing nervous system.

- They lose their authentic self. They become so focused on avoiding punishment that they stop expressing their real thoughts and feelings.

- The behavior doesn’t actually change. You might notice the same issues keep popping up in different ways or behavior getting worse over time as the child’s emotional needs go unmet.

What Real Cooperation Looks Like

When children feel safe and connected, they naturally want to cooperate with the people they love. Real cooperation looks different from fear-based compliance:

- Your child might still protest or have big feelings, but they ultimately work with you to solve problems

- They come to you when they’re struggling instead of hiding their emotions

- They show genuine remorse when they hurt someone, not just fear of getting in trouble

- Their behavior improvements are more lasting, even though they’ll still make mistakes as they develop skills like impulse control, cause-and-effect thinking, and frustration tolerance

- They maintain their personality and opinions while still following family rules

Breaking the Cycle

If you’ve been using time-outs and see this pattern, don’t panic.

Attachment relationships are resilient and repairable. Kids are incredibly forgiving when we change our approach and start meeting their emotional needs.

The key is understanding that your child’s challenging behavior isn’t manipulation or defiance – it’s communication. They’re telling you something is wrong, and they need help, not punishment.

Co-Regulation Research

Here’s what the science tells us about how children actually learn to manage their emotions.

Dr. Stuart Shanker, a leading researcher on self-regulation, explains that before kids can self-regulate, they must first learn through co-regulation with a calm, attuned caregiver. This knowledge is backed by decades of neuroscience research.

Co-regulation is an interactive process where a regulated adult helps a dysregulated child return to a state of calm.

Dr. Ed Tronick’s research shows that this process begins in infancy and continues throughout childhood development. Even adults rely on co-regulation. We go to our friends, families, and spouses to seek comfort and get through stressful situations all the time. That’s co-regulation. It’s a normal thing everybody does.

The Science Behind Co-Regulation

Dr. Megan Gunnar’s research on stress and regulation demonstrates that when children experience stress (which includes being upset, frustrated, or overwhelmed), their cortisol levels spike.

However, when a calm adult stays present and helps them regulate, those stress hormones return to normal much faster than when children are left to calm down alone.

Studies show that children who experience consistent co-regulation develop stronger neural pathways for emotional regulation. This means their brains literally wire differently, leading to better long-term behavioral outcomes than children who are expected to regulate independently before they’re developmentally ready.

What Co-Regulation Looks Like

Co-regulation isn’t about fixing your child’s emotions or making them stop crying.

It’s about staying calm and present while they experience their big feelings.

This might include:

- Taking slow, deep breaths while sitting near your child

- Speaking in a calm, soothing voice

- Offering physical comfort, if your child wants it

- Validating their emotions (a great way to do this is through emotion coaching)

- Staying patient while their nervous system settles

Why Co-Regulation Works When Time-Outs Don’t

The American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes that children’s stress response systems need the support of caring adults to develop properly.

If we regularly isolate kids during their most dysregulated moments because we’ve deemed that behavior as bad, we’re taking away the thing they need most.

The Long-Term Benefits

Children who experience consistent co-regulation don’t just behave better in the moment.

Studies show they develop:

- Stronger emotional vocabulary and self-awareness

- Better stress tolerance and resilience

- More secure attachment relationships

- Enhanced problem-solving abilities

- Greater empathy and social skills

Want to learn more about implementing co-regulation in your daily life? Check out our comprehensive guides on the dos and don’ts of co-regulation and co-regulation for behavior support.

This approach takes patience and practice, but the research is clear: co-regulation builds the foundation for lifelong emotional health and strong relationships.

Why Time-Ins Work Better Than Time-Outs

Emotional Safety vs. Emotional Wounding

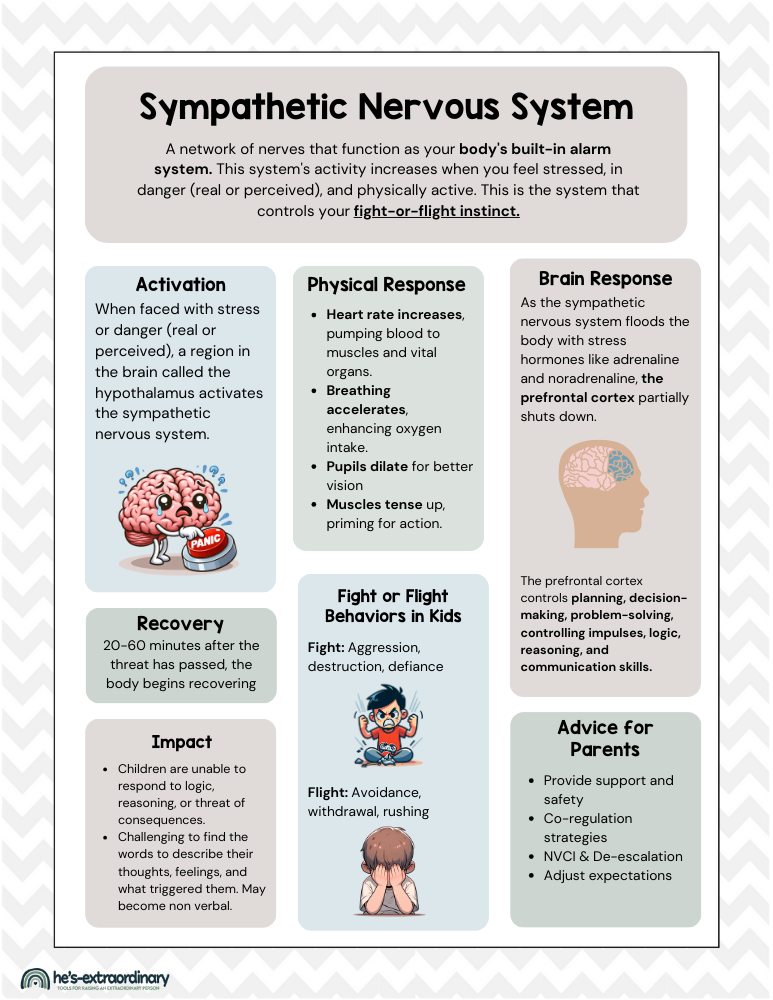

Time-outs trigger what Dr. Neufeld calls the “alarm system”—the same system activated during real threats to survival. This triggers the fight-or-flight response.

While this alarm creates immediate compliance through fear, it damages the child’s sense of safety and connection.

Time-ins, on the other hand, communicate safety and unconditional love even during difficult moments. This emotional safety is the foundation for all learning and growth.

Skill Building vs. Behavior Suppression

Time-outs focus on stopping unwanted behavior through consequences and control.

Kids learn, “Don’t do this, or you’ll be isolated,” but they don’t learn what to do instead or how to manage the feelings that led to the behavior.

Time-ins teach actual skills: how to recognize emotions, how to calm your body, how to communicate needs appropriately, and how to problem-solve conflicts.

Long-Term Relationship Impact

Research from the National Institute of Mental Health shows that children who experience frequent isolation-based discipline are more likely to develop anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems later in childhood.

Time-ins strengthen the parent-child relationship during difficult moments, building trust that lasts into adolescence and beyond.

Understanding Why Children Misbehave

Before implementing time-ins, you need to understand what’s really going on when your child acts out.

Misbehavior as a Symptom of Lagging Skills

Dr. Stuart Ablon, founder of Think Kids, introduced the concept that “kids do well if they can.” Your child doesn’t behave poorly because they want to get in trouble or test your limits.

Poor behavior is a sign that your child lacks the skills required to handle the situation appropriately.

Common Lagging Skills Include:

- Problem-solving skills – figuring out how to get needs met appropriately

- Impulse control – pausing before acting on immediate desires

- Emotional regulation – managing big feelings without being overwhelmed

- Cognitive flexibility – adapting when plans change, or things don’t go as expected

- Communication skills – expressing needs and feelings with words instead of actions

Most of these lagging skills fall under executive functions, which don’t fully develop until early adulthood.

The Role of the Nervous System

When children feel overwhelmed, threatened, or dysregulated, their nervous system shifts into survival mode. In this state, the thinking brain goes offline, and the reactive brain takes over.

This is why logical consequences and reasoning don’t work when children are upset. They literally cannot access the part of their brain needed for learning until they feel safe and calm again.

Time Ins by Age Group

Different developmental stages require different approaches to time-ins.

Ages 18 Months – 3 Years

What’s Happening Developmentally:

- Limited language skills

- Big emotions with no regulation skills

- Learning cause and effect

- Strong need for routine and predictability

Time In Approach:

- Keep it simple and brief (2-5 minutes)

- Focus on co-regulation through your calm presence

- Use simple language: “I’m here. You’re safe. Let’s breathe together.”

- Offer comfort objects or sensory tools

- Validate feelings: “You’re upset that playtime ended.”

Example Script: “It makes sense that you’re upset about it being bedtime because you were having so much fun playing blocks, and it’s hard when we have to stop doing something fun. I’m going to sit with you until you feel better. We can take some deep breaths together.”

Ages 3-5 Years

What’s Happening Developmentally:

- Emerging language skills

- Beginning to understand emotions

- Testing boundaries and independence

- Still learning impulse control

Time In Approach:

- Introduce simple emotion vocabulary

- Use visual aids like feelings charts

- Practice calming strategies together

- Begin simple problem-solving conversations

- Duration: 5-10 minutes

Example Script: “It looks like you’re feeling frustrated because your tower fell down. That’s a big feeling. Let’s go to our calm-down space and figure out what might help you feel better.”

Ages 6-12 Years

What’s Happening Developmentally:

- Better language and reasoning skills

- Understanding of social rules and expectations

- Increased emotional awareness

- Beginning to internalize regulation strategies

Time In Approach:

- Engage in deeper conversations about feelings and choices

- Teach specific coping strategies

- Include problem-solving and planning

- Help them identify triggers and early warning signs

- Duration: 10-20 minutes as needed

Example Script: “I can see you’re feeling angry that your sister touched your project without asking. That would be upsetting – you worked hard on that. It’s okay to feel mad about it. Let’s sit here together, and I’ll help you get your body feeling calmer. Would you like to try some deep breathing with me, or do you just want me to sit quietly with you?

How to Implement Time-Ins Step-by-Step

Step 1: Create Your Calm Down Space

Your time-in space should be comfortable, calming, and consistently available.

This isn’t a time-out punishment corner; it’s a safe haven for emotional regulation.

Essential Elements:

- Comfortable seating for both you and your child

- Soft lighting or natural light

- Calming sensory tools (stress balls, fidgets, weighted lap pad)

- Visual aids (feelings chart, breathing cards)

- Books about emotions appropriate for your child’s age

- No distracting toys or screens

Check out this guide for more: How to Make The Ultimate Calming Corner

Step 2: Introduce the Concept During Calm Moments

Don’t introduce time-ins for the first time during a crisis. When your child is regulated and happy, show them the space and explain how it works…or better yet, have them help you create the space.

“This is our calm down space. When we have big feelings, we can come here together to help our bodies feel better. We can use our breathing cards, squeeze our stress ball, or just sit together until we feel calm.”

Step 3: Practice Regulation Strategies While Calm

You can’t teach someone to swim when they’re drowning, and you can’t teach self-regulation skills during dysregulation.

You need to practice regulation strategies with your child when they’re calm. Different things work for different people, and it can take time before kids learn to use these techniques in tough moments. So, you need to be persistent with this.

Some strategies to try:

- Deep breathing techniques

- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Mindfulness exercises

- Using an emotion wheel

- 5-4-3-2-1 Grounding

For even more ideas, visit this list of 120+ self-regulation strategies for kids.

Step 4: Recognize Early Warning Signs

Time-ins work best when implemented early, before full dysregulation occurs.

Signs of dysregulation can vary from one child to the next, and you’ll know your child better than anyone else. But here are some early signs to look out for.

- Changes in voice tone or volume

- Physical tension or restlessness

- Increased impulsivity

- Difficulty following directions

- Beginning to argue or protest

Step 5: Implement Your Time-In Plan

Your plan should include:

- Recognition: “I can see you’re getting frustrated.”

- Invitation: “Let’s take a time-in together so we can help your body feel calm.”

- Movement: Guide them to your calm-down space

- Co-regulation: Stay present and use your practiced strategies

- Check-in: “How is your body feeling now?”

- Return: Go back to the original situation when they’re ready

Step 6: Follow Through Consistently

Consistency is key for time-ins to become effective.

Every caregiver should use the same language and approach.

Scripts and Language for Time Ins

Invitation Language:

- “It looks like you need some help with those big feelings.”

- “Your body seems really upset right now. Let’s take a time in.”

- “I can see this is hard for you. Let’s go to our calm space together.”

During the Time In:

- “I’m right here with you.”

- “You’re safe. We’re going to figure this out together.”

- “Let’s take some slow, deep breaths.”

- “What is your body telling you right now?”

Validation Statements:

- “It makes sense that you’d be upset about that.”

- “Those are really big feelings for a little body.”

- “I can see how much you wanted that to work differently.”

Returning to the Situation:

- “How is your body feeling now?”

- “Do you feel ready to try again?”

- “What might help this go better next time?”

Common Parent Concerns and Questions About Time-Ins

“Am I Rewarding Bad Behavior?”

This concern comes from the misconception that love and attention are rewards to be earned rather than basic needs to be met unconditionally.

Time-ins don’t reward misbehavior—they address the underlying need that caused the behavior. When kids feel truly seen and supported, they’re less likely to act out to get attention.

Research shows that children who receive consistent emotional support during difficult moments develop better behavior over time, not worse.

“Will This Spoil My Child?”

Setting boundaries and having expectations doesn’t disappear with time-ins.

You’re still addressing behaviors, holding boundaries, and helping your child learn appropriate ways to handle situations.

The difference is that you’re teaching skills rather than relying on fear or shame. Children who learn through connection and skill-building develop stronger internal motivation to behave well.

“What If My Child Resists or Refuses Time-Ins?”

Resistance is normal, especially if you’ve used time-outs before.

Strategies for Resistance:

- Stay calm and consistent

- As long as you’re somewhere safe, co-regulate where you are rather than moving your child if they refuse to go to the space

- Start with very short time ins (2-3 minutes)

- Let your child help design the calm-down space

- Practice during calm moments first

- Model taking time-ins for yourself

“This Takes Too Much Time”

Time-ins do require an initial time investment, but they save time in the long run. Children who learn regulation skills have fewer meltdowns and recover faster from upsets.

Most time-ins last 5-15 minutes, which is often shorter than dealing with the aftermath of punishment-based discipline.

“What If My Child Wants to be Left Alone?”

It is important to balance respecting your child’s autonomy with not defaulting back to isolation.

Here are some options and considerations:

- For younger kids (3-6): Sometimes, when kids say “leave me alone,” they’re overwhelmed, not actually wanting abandonment. You could say: “I hear that you want space. I’m going to sit right here [point to a spot nearby but not touching] so you know I’m here when you’re ready.”

- For older kids (6-12): They may genuinely need some physical space to regulate. You could say: “I can see you need some space right now. I’m going to step back, but I’ll be close by if you need me. Let me know when you want me closer.”

Key principles:

- Respect the request for physical space

- But don’t leave them completely alone/isolated

- Stay nearby and available

- Make it clear you’re not going away as punishment

- Let them control when they want you closer again

The difference from time-outs: You’re not sending them away as consequences. They’re asking for space, you’re respecting it, but you’re staying emotionally available and physically nearby.

Some kids genuinely do regulate better with some physical space while still knowing their caregiver is accessible.

Using Time-Ins with Neurodivergent Children

Neurodivergent children often have unique sensory, communication, and regulation needs that require adapted approaches to time-ins.

Sensory Considerations

Many autistic children, children with ADHD, and those with sensory processing differences have specific sensory needs that affect their ability to regulate their emotions.

Adaptations Might Include:

- Offering noise-canceling headphones or ear defenders

- Providing weighted lap pads or compression tools

- Adjusting lighting to reduce overwhelm

- Including proprioceptive activities (heavy work)

- Respecting sensory aversions (no forced hugs)

Communication Adaptations

Some neurodivergent children may have difficulty expressing their needs verbally or understanding complex language during dysregulation.

Helpful Strategies:

- Use visual supports (picture cards, emotion charts, posters of calming strategies)

- Offer alternative communication methods

- Simplify language during distress

- Allow extra processing time

- Respect different communication styles

Understanding Neurological Differences

Neurodivergent children may have differences in emotional regulation, executive functioning, and sensory processing that affect how they experience and recover from dysregulation.

Time-ins should focus on supporting their unique nervous system needs rather than trying to make them regulate like neurotypical children.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Using Time-Ins as Hidden Punishment

If you’re frustrated or angry when implementing a time in, your child will sense this, and the strategy becomes punitive rather than supportive.

Take a moment to regulate yourself before offering a time-in to your child.

Trying to Teach During Dysregulation

As I mentioned earlier, when kids are upset, their thinking brain is offline. They can’t learn in this state. Save conversations about choices and consequences for when they’re calm and regulated.

Pause other demands and expectations.

During the time-in, focus only on co-regulation and emotional support.

Being Inconsistent

If you use time-ins sometimes and time-outs other times, your child will feel confused and insecure about what to expect.

Commit to the approach and use it consistently across all caregivers.

Rushing the Process

Every child regulates at their own pace. And how long it takes to feel calm again might change for your child from one situation to the next. Our feelings don’t have a set time limit.

Don’t pressure them to “hurry up and feel better” or cut the time-in short because you’re impatient.

Follow their lead on when they’re ready to re-engage.

Troubleshooting When Time-Ins Aren’t Working

Your Child Won’t Come to the Calm Down Space

- Meet them where they’re at and do the time-in there

- Start by taking time-ins yourself and inviting them to join you

- Make the space more appealing with their help

- Begin with very brief time-ins during minor situations

- Stay nearby even if they won’t sit with you

Time-Ins Seem to Increase Behavior Issues

- Are you implementing true time-ins (supportive, not punitive)?

- Make sure you’re addressing the underlying need, not just the behavior

- Consider if there are unmet needs (hunger, tiredness, overstimulation)

- Consult with a pediatric mental health professional if concerns persist

Other Caregivers Won’t Use Time-Ins

- Share research and articles (like this one) about the benefits

- Offer to demonstrate the technique

- Start small with one other caregiver

- Be patient—changing discipline approaches takes time

Building a Complete Positive Discipline Approach

Time-ins work best as part of a comprehensive positive discipline approach that includes:

Proactive Strategies:

- Clear, consistent expectations

- Predictable routines and structure

- Regular one-on-one connection time

- Teaching emotional regulation skills during calm moments

Responsive Strategies:

- Natural consequences when appropriate

- Problem-solving together

- Emotion coaching and validation

- Repair and reconnection after conflicts

Relationship Building:

- Regular special time with each child

- Family meetings and collaborative rule-making

- Celebrating effort and growth, not just outcomes

- Modeling the emotional regulation you want to see

The Long-Term Benefits of Time-Ins

Children who experience time-ins rather than time-outs show better outcomes in multiple areas:

Emotional Development:

- Stronger emotional vocabulary and awareness

- Better self-regulation skills

- Increased empathy and social skills

- Lower rates of anxiety and depression

Behavioral Outcomes:

- Fewer aggressive behaviors

- Better problem-solving skills

- Increased cooperation and compliance

- Stronger internal motivation

Relationship Quality:

- Deeper trust with parents

- Better communication skills

- Stronger family relationships into adolescence

- More secure attachment patterns

Getting Started Today

You don’t need to wait for the perfect setup to begin using time-ins. Start with these simple steps:

- Choose a basic calm-down space – even a corner with pillows works

- Practice deep breathing together during a good moment

- The next time your child is mildly upset, offer: “Let’s take a time in together.”

- Stay present and calm while they regulate

- Notice what works and build from there

Remember, this is a skill that takes practice for both you and your child. Be patient with the process and celebrate small wins along the way.

Time-ins are a way of parenting that honors your child’s developing brain, respects their emotional world, and builds the kind of relationship that will support them throughout their lives.

Choosing connection over isolation doesn’t just improve behavior; it helps kids develop the emotional intelligence and regulation skills they’ll need to navigate relationships, handle stress, and make good decisions for the rest of their lives.

Your child doesn’t need to be fixed, controlled, or scared into compliance. They need to be seen, understood, and supported as they learn to navigate their complex inner world.

Time-ins give you the tools to do exactly that.