10 Ways to Support Self-Advocacy (Even When It Sounds Like “Go Away!”)

Summer break is here, or just around the corner, and your child is probably taking a break from all of their academic work. Summer is a time to have fun, but you can also use this extra time with your child to support some skills that don’t necessarily receive as much focus during the school year but are still extremely important.

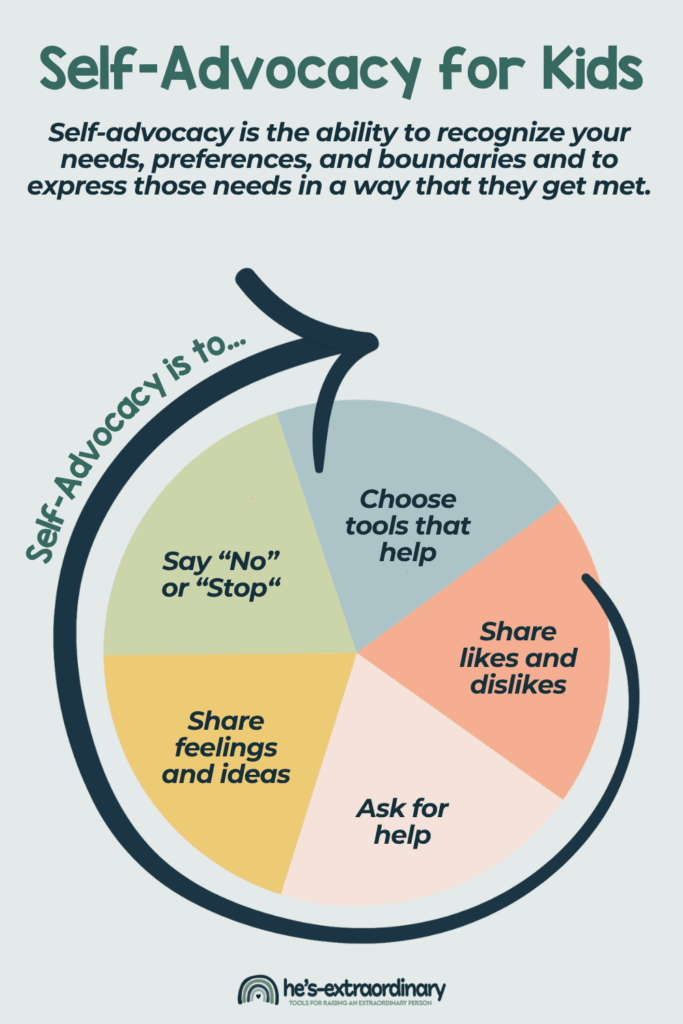

One of those skills is self-advocacy. Self-advocacy is the ability to recognize your needs, preferences (especially sensory preferences), and boundaries and to express those needs in a way that they get met.

It isn’t a skill that kids master overnight, and it doesn’t always look like neatly worded sentences. In fact, it can be really messy.

Sometimes, it looks like a kid shouting “No!” and running away. Sometimes, it could be them covering their ears when something is too loud. Or, it might be them whispering “stop” under their breath when their sibling bothers them. At other times, it’s a perfectly worded sentence, such as “It’s too loud in here; can I have my headphones, please?”

All of these examples are valid forms of self-advocacy, but with your help and extra practice, kids can improve their delivery over time.

This article looks at 10 ways that you can help your child grow and improve their self-advocacy skills at home.

This is so important because when our kids are young, we are their voice, but we can’t be with them all the time. As they get older, they spend more time away from us, and they need to be able to advocate for themselves with their peers and with the other adults around them.

1. Narrate Your Own Needs Out Loud

Kids learn a lot about what they should do and what they should say by watching the things the adults around them do and say.

So, one of the easiest ways that you can encourage developing self-advocacy skills is by narrating the reasons why you’re doing all of the things that you’re doing.

For example:

- “I don’t like the smell in here. I’m going to open the window.”

- “My feet are really sore from working all day. I’m going to relax on the couch to rest them.”

- “The sun is really bright. I’m going to get my sunglasses.”

All of these are things that we’re doing for ourselves to meet our own needs. Narrating allows kids to see, understand, and learn to communicate for themselves over time.

Sometimes, we have to say no to our kids, and “no” can be a challenging word for them to hear. However, it’s important to explain the reasons behind our decisions, especially when it relates to personal boundaries. This not only helps them understand but also models self-advocacy. For example, you might say, “No, I can’t take you to the playground right now because I have a headache and need some rest,” or “No, I don’t want to play with slime because I really dislike the way it feels on my hands.”

When we tell our kids no in this context, we also create an opportunity to counteroffer, modeling even more self-advocacy. For example, you could say, “I bet some extra cuddles would really help my headache. You could lie down with me and play on your tablet if you’d like,” or “I’d love to watch you play with the slime. I enjoy seeing how you stretch it out, making it look like sticky webs between your fingers.”

2. Pause Before Correcting Their Feelings or Sensations

Before someone can effectively advocate for themselves, they must be able to accurately identify their internal states and emotions. This is a skill that develops gradually and takes time to master.

Just like when kids are learning how to read, they don’t always sound out a word correctly; similarly, they may not label their feelings or body sensations accurately. This doesn’t mean they are wrong; it just means they are practicing.

For example, if your child says, “I’m still hungry,” it’s possible that what they really mean is, “That ice cream tasted sooooooooooo good!”

In these situations, it’s important to avoid saying things that dismiss or invalidate their feelings.

Phrases like “You can’t be still hungry after everything you just ate,” “That didn’t hurt,” or “You’re not mad; you’re just tired” can undermine their self-perception.

When we dismiss or invalidate a child’s internal experiences, even if we suspect their report is inaccurate, we teach them to question themselves or ignore their feelings. This can lead to self-doubt and may trigger power struggles as they defend themselves and push back in the moment.

Instead, you might respond with something like, “You’re still hungry? Let’s see what snacks we have. We’re done with the ice cream for now, but you can pick something else.”

Later, when everyone is calm and collected, you can revisit the situation and gently ask your child a question out of curiosity, such as, “Do you think you were still hungry earlier, or did that ice cream just taste so good?”

Approaching the topic with curiosity rather than discipline helps children reflect on their experiences, allowing them to become better at detecting their internal states and emotions over time.

3. Recognize That Self-Advocacy Doesn’t Always Involve Words

Since self-advocacy is a skill that develops gradually over time, it’s not always going to be a well-communicated and thought-out sentence. Self-advocacy takes on many forms and varies depending on your child’s age, their communication style, or how regulated they are in the moment.

Here are a few different examples of self-advocacy that show what it may look like from different stages

Sensory-Driven Instincts

This is the foundation of self-advocacy. It manifests as instinctual behavioral responses to a situation. These responses might include crying, running away, covering their ears or eyes, or even having meltdowns.

When a child exhibits these behaviors, they are often labeled as “bad behavior” or “non-compliance.” However, it’s important to understand that your child is not consciously deciding to behave this way; rather, these are intuitive actions to defend themselves from something that feels distressing.

It’s important to understand that these actions are a form of communication indicating that something is unsettling or intolerable for your child. Instead of focusing on controlling the behavior, it’s more helpful to focus your attention on understanding the underlying feelings and needs.

Once those needs are met, the challenging behavior often subsides.

Your child’s nervous system is signaling that something is not okay, and it is your job to decode what that is and address the need.

For example, if your child screams every time you try to enter a public bathroom, they may be distressed by the sound of the toilet flushing or the loud hand dryer. So rather than expecting them to go into the bathroom anyway and “just deal with it,” you could try offering them noise-canceling headphones to help minimize the auditory stress.

Gestures and Nonverbal Communication

As children develop their communication skills, they start using intentional gestures to express their needs. This can include actions like pointing to an object, pulling away from something they don’t want, or handing someone something they need, like their headphones or water bottle.

These nonverbal ways of expressing themselves are purposeful and important, even if they don’t use full spoken sentences. They are just as valid ways to advocate as using spoken words.

Simple Verbal Advocacy

This form of self-advocacy involves using short, clear phrases to communicate when something is wrong or when they want something.

For example, your child might say “no,” “too loud,” or “I don’t like that.” Others may repeatedly press a button on their AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) device, such as “stop, stop, stop.”

This is a great example of a child who recognizes that something doesn’t feel right but may not yet have the full communication skills or self-awareness to articulate what they need or what the solution is.

It’s also important to remember that sometimes these words can come out very abruptly, especially during moments of dysregulation when their thinking brain is offline. This is because during uncomfortable situations, it becomes more challenging to communicate, and it takes greater effort to advocate for their body and express their emotions.

This can be a difficult skill for children to develop, so your child might say things like “I hate that” or “Go away.”

Instead of focusing on correcting how they phrased their message, it’s best to validate their need by saying, “I see that you didn’t like that” or “I understand.”

When your child is calm, you can revisit the situation and offer alternative language for them to use next time. However, in the moment, the message they are trying to convey is more important than the way they phrase it.

Expressive Self-Advocacy

Over time, and with the right support, kids develop the skills they need to express their wants and needs with greater complexity. This doesn’t always involve spoken language; they might communicate through speech, sign language, typing, or using an AAC device. All of these forms of communication can be used for expressive self-advocacy.

For example, children can use full sentences to express what they’re feeling and what they need, such as:

- “That sound is hurting my ears; can we turn it down?”

- “I have a lot of energy; I need to move.”

- “I’m thirsty; I need a drink.”

As you can see, self-advocacy isn’t always thoughtful, respectful communication. All of these different levels of self-advocacy look different.

For instance, a child who covers their ears and screams to express discomfort is just as valid in their self-advocacy as another child who calmly asks, “That’s too loud; can you please turn it down?”

Recognizing and accepting these different expressions of self-advocacy can encourage children to advocate for themselves more effectively as they learn and grow.

4. Offer Meaningful Choices

One simple way to help your child practice advocating for their preferences is by offering them real, age-appropriate choices. This approach builds their autonomy and reinforces the idea that their voice matters. It also helps them learn to recognize their internal sensations and emotional states while experimenting with different ways to address those feelings.

You can start with simple, small choices, like asking, “Do you want strawberries or blueberries with your yogurt?” or “Would you rather go to the park or the beach today?”

For older kids or those who are more comfortable making decisions, you can offer open-ended options, like “What would you like to do with your free time today?” or “Do you know what might help you feel better right now?”

Giving children the chance to make choices and observe the outcomes helps them practice self-advocacy and better understand their preferences, as well as what accommodations may help them in different situations.

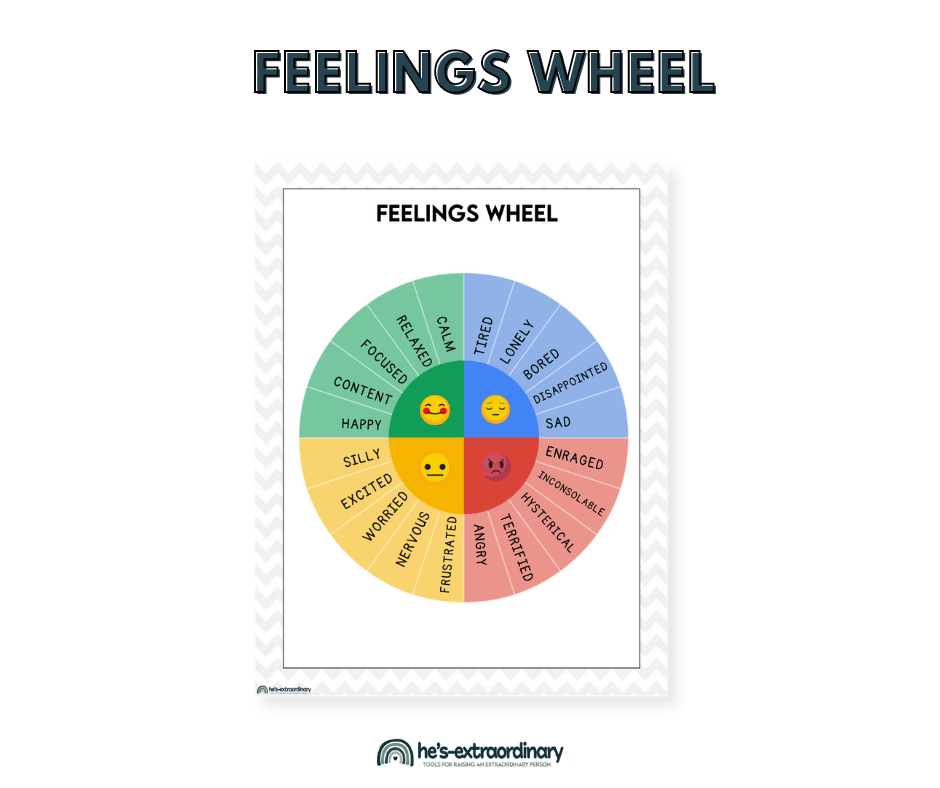

5. Use Visual Tools and Supports

Visual supports are valuable tools for everyone, both kids and adults alike. Adults often use visual supports to create tangible anchors for themselves, like calendars, checklists, or to-do lists.

These supports are especially helpful for understanding abstract concepts like time, expectations, or internal emotions. For children, visual supports can provide added predictability, especially during times like summer break, when their routines change, helping to reduce anxiety and making communication more accessible.

Additionally, visual supports empower children to advocate for themselves, even if they lack the words to express their needs.

Examples of visual supports include:

- A card that says “I need a break,” which children can hand to an adult.

- A visual menu of sensory tools or coping strategies they can choose from.

- Picture charts for making choices regarding snacks, activities, or bedtime routines.

- Feelings charts or an emotion wheel to help express their internal states.

It’s important to note that visual supports are not only beneficial for non-speaking children. Even kids who are highly verbal can benefit from these communication tools, especially when they are dysregulated, tired, overwhelmed, or overstimulated.

Visual tools do not replace communication. Visual tools enhance communication. Visual tools are communication.

They enable kids to express their needs more effectively, which can significantly reduce challenging behaviors and dysregulation. Using visual tools is an excellent strategy for individuals of all ages and abilities.

These supports make communication more accessible, provide children with greater autonomy, offer clarity, and create more opportunities for them to be understood.

6. Reflect What You See

Before kids can advocate for their needs, they first need to understand what those needs are. This kind of self-awareness doesn’t develop automatically; it’s a skill that children will build over time through experience. There are many ways to help kids build self-awareness, and if you’re interested in learning more, you can find additional resources here.

One gentle and effective approach to help your child develop self-awareness is to reflect on your observations out loud, without judgment.

When you do this, avoid labeling their emotions or behaviors as “good” or “bad,” and don’t approach it in a way that feels controlling or corrective.

Instead, offer a possible interpretation from a place of curiosity, not discipline. Think of it as holding up a mirror—not to shame or correct your child, but to help them connect with what their body may be trying to tell them.

For example, you might say:

- “I see you pulled away; maybe you don’t want to be touched right now.”

- “Your fists are clenched really tight; I wonder if you’re feeling mad.”

- “I see you hiding under the blanket; do you need some quiet time?”

None of these phrases is a demand; they are invitations.

You’re not instructing your child to stop doing something or telling them to calm down; you’re just acknowledging your observations and trying to help them figure out their feelings.

Some kids may nod in response, while others might deny your observations or provide a completely different explanation. If you misinterpret their feelings, that’s okay. What matters is that you’re modeling an important idea: emotions and sensations are valid and worth noticing, and you are a safe person who cares about them and wants to understand.

Over time, your child may start offering reflections of their own. They might say something like, “My hands are doing that tight, squeezy thing again.”

This shows you that they’re connecting the dots between their physical sensations and their emotions, like recognizing that clenched fists often signify anger.

This type of reflection lays the groundwork for self-advocacy, but it’s important to do this without pressure, shame, or expectations.

It should be rooted in curiosity to help your child tune into their own body, learn to trust their signals, and eventually articulate what they are experiencing—whether through words, signs, or gestures.

7. Reinforce and Celebrate Self-Advocacy, Even When Delivery Isn’t Perfect

Self-advocacy takes a lot of courage, especially for a child. It can be scary for them to express their feelings and needs, especially if they’re unsure how adults will react.

This is why it’s so important to notice your child’s efforts and reinforce the message, even if the delivery isn’t perfect.

It’s important to set realistic expectations and understand your child isn’t always going to use the right words or the right tone of voice to convey their message.

They might yell, “STOP IT!” instead of saying, “I didn’t like that,” but that response is still really valid communication and an attempt at self-advocacy.

So, rather than focusing on whether or not your kid used the right word or the right tone of voice to tell you how they’re feeling, just focus on the fact that they advocated for themselves because that is the skill that you want to grow.

You can validate their effort to self-advocate without validating inappropriate language use or inappropriate tones of voice. For example, you might say, “You want me to stop…That was really clear.”

It’s okay to address their language later when they are calm. In the moment, the priority is to acknowledge their feelings and efforts.

Later, you can guide them on how to express themselves more appropriately, such as saying, “Earlier, you said STOP IT when that noise got really loud. I’m really glad that you told me it was too loud, but next time you could try saying something like ‘it’s too loud in here and I need a break.’ Can we practice saying that together now?”

Celebrating their efforts without demanding perfection from them in the moment helps kids build trust and feel safer communicating, even when choosing the right words is still a work in progress.

This shows your child that their voice matters. The goal shouldn’t be to mold your child into a polite, compliant communicator; the goal is to support them in expressing their needs effectively.

8. Give Space to Problem Solve

The ultimate goal of self-advocacy isn’t just to express what’s wrong; it’s also about presenting solutions to those problems so that your needs can be met in a way that works for you.

One effective way to help your child build this skill is by involving them in problem-solving when things aren’t going smoothly. Rather than rushing in to fix everything for them, invite them to participate in the process of finding possible solutions together.

This doesn’t mean leaving your child to figure things out on their own—especially if they are still developing this skill. It means collaborating with your child and letting them know that their perspective matters.

For example, you could say, “I know you really didn’t want to leave the park when it was time to go. Let’s talk about what we can do next time to make it easier to leave.” It’s also important to validate their feelings: “It makes sense that you didn’t want to leave the park—being there is really fun!” Even if your child can’t articulate a verbal response, you can offer them choices or narrate your thoughts out loud. This shows them that their preferences are valid and that you are willing to work with them to make difficult situations more manageable, rather than just expecting them to cope with it.

This type of collaborative problem-solving lays a strong foundation for future self-advocacy and shows your child how they can use their voice not only to express discomfort but also to influence their environment, making it more comfortable for themselves.

9. Respect Boundaries

Sometimes, self-advocacy skills aren’t encouraged as much as they should be because self-advocacy often involves saying no to things that you don’t want to do.

As a result, adults often perceive a child’s self-advocacy as non-compliance if they’re expressing a desire to stop or refusing to participate in an activity that an adult would like them to do. However, drawing boundaries is a key part of healthy communication.

Self-advocacy must include the right to say no. This doesn’t mean that kids should always get their way or should never have to do things they don’t want to do. Some responsibilities, particularly those involving health or safety, are non-negotiable. But, how we respond to when a child says no can teach them whether their boundaries will be respected or dismissed.

Instead of saying something like, “Too bad, you have to do that,” or “You don’t get a choice… because I said so,” you might say, “I understand that you don’t want to do this, but it’s still something we need to take care of. Let’s talk about how and why.“

This allows you to help your child understand the importance of the task—like explaining that not taking care of our teeth can affect our overall health.

If your child expresses a desire not to engage in a certain activity, such as hugging, respect that boundary. You can say, “Oh, you don’t want to hug right now? That’s okay; I can just wave instead.”

These small moments reinforce to children that it’s acceptable to have limits and that saying no won’t get them in trouble. It helps kids see that they won’t be forced to go beyond their comfort zone simply because an adult has the authority.

Balancing your own boundaries—understanding that a child may not want to brush their teeth (and it’s okay to not want to do it) while maintaining that it is an important task—builds trust in your relationship. This trust encourages children to continue self-advocating, even when it is difficult.

10. Expect Progress, Not Perfection

Just like with any developing skill, learning to self-advocate isn’t going to follow a straight path. There will be times when your child does an excellent job at self-advocacy, and there will be times when the process feels messy.

They are going to choose the wrong words or use the wrong tone of voice sometimes.

One moment they might say, “I need some space; I’m feeling overwhelmed,” and the next day they might yell, “GO AWAY!”

There may be times when your child feels so overwhelmed that they can’t remember the words they practiced. However, this doesn’t mean they aren’t trying or that they’re doing it wrong; it simply means that they are human and they are still learning.

One of the most powerful things we can do to help our kids is to respond with curiosity and connection rather than solely focusing on correction.

These are BIG feelings, and we should say, “I’m here for you. Let’s figure out together what will help next time.”

It’s important to recognize that self-advocacy isn’t just about being perfectly polite and composed at all times; it’s about learning to listen to your body, trust your instincts, and speak up for yourself in whatever way is necessary.

Sometimes that expression is clear and calm; other times, it may be loud, raw, and messy.

The goal isn’t to eliminate the mess but to meet your child in their mess with understanding, not shame, and to continually show them that their voice is always welcome.

- Article: Teaching Self-Advocacy Skills to Neurodivergent Kids

- Printable: Self-Advocacy Guide for Kids

- Printable: Self-Advocacy Communication Cards

- Article: Teaching Kids to Advocate for Their Sensory Needs

- Article: How Can an OT Help Your Child with Self-Advocacy