How Your Child’s Nervous System Impacts Emotional Regulation and Meltdowns

What’s inside this article: An in-depth look at how the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system work, what occurs when the stress response is activated, and how it impacts your child’s ability to regulate emotions and their cognition. Plus, key advice for parents on how to respond to their child’s behavior most effectively to support emotional regulation.

The nervous system includes the brain, spinal cord, and a complex network of nerves. This system sends messages back and forth between the brain and the body.

The nervous system is made up of the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system:

- The central nervous system includes the brain and spinal cord.

- The peripheral nervous system includes the nerves that run throughout the whole body.

The autonomic nervous system is a component of the peripheral nervous system that regulates involuntary physiological processes, including heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion, and more.

It contains three anatomically distinct divisions:

- the sympathetic nervous system

- the parasympathetic nervous system

- the enteric nervous system

Understanding the nervous system can help you better understand your autistic child and help them when they are struggling with dysregulation and meltdowns.

This article mainly focuses on the function of the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system.

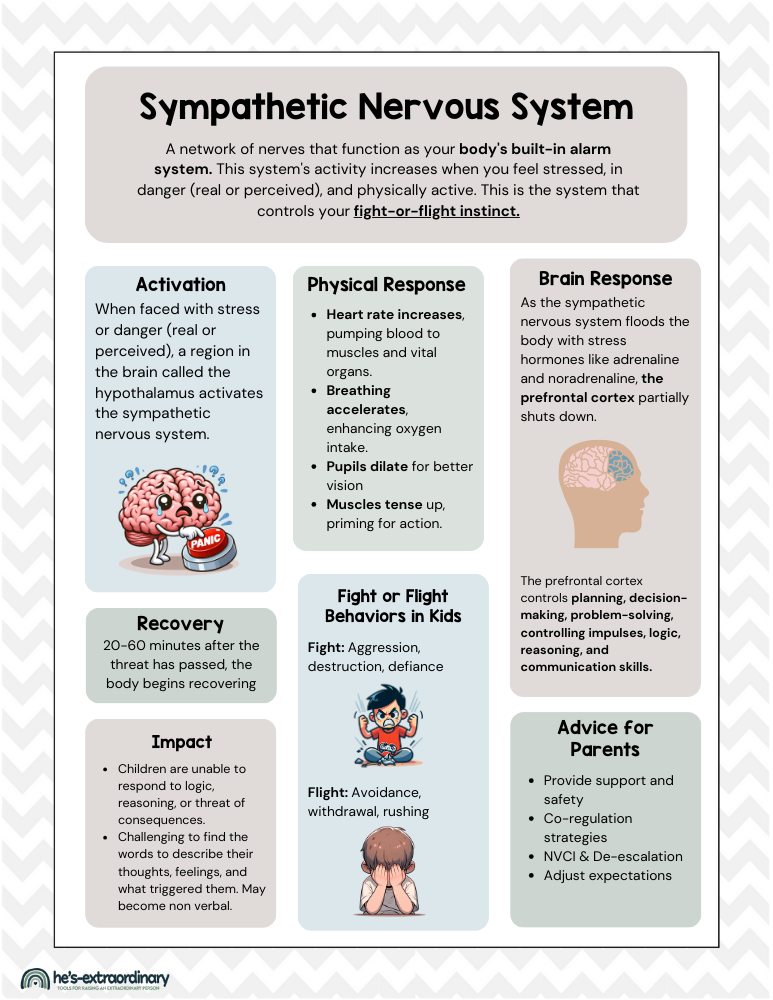

The Sympathetic Nervous System

The sympathetic nervous system is a network of nerves that function as your body’s built-in alarm system. This system’s activity increases when you feel stressed, in danger (real or perceived), and physically active.

This is the system that controls your fight-or-flight instinct.

It’s very important to understand the sympathetic nervous system if you want to understand what’s taking place when a child is emotionally dysregulated or having a meltdown.

How the sympathetic nervous system works:

Any time you (or your child) are in a situation that is stressful or feels threatening, the sympathetic nervous system is activated.

Remember, this is not something we have conscious control over. Simply telling ourselves we are safe cannot stop the automatic response that happens when the sympathetic nervous system is activated.

Trigger and Activation:

When faced with stress or danger (real or perceived), a region in the brain called the hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system.

It’s basically like your brain says, “Okay, this might not be safe,” or “This is really stressful, and I don’t know how to handle it,” and pushes a panic button (a rapid release of cortisol and adrenaline), signaling that it’s time to prepare for a potential threat.

Many things can trigger the activation of this system. It all depends on your individual triggers. A sudden loud noise, yelling, unexpected events or changes to routine, an unfamiliar environment, or doing something new and challenging to you are just a few common triggers, but it could be anything stressful.

Transmission of Signals:

This activation sends a rapid message down your spinal cord to various parts of your body. This is your nervous system’s way of distributing orders quickly and efficiently.

As soon as this message is sent, physiological changes happen throughout your body.

Physical Response:

Once the message is received, your body undergoes a transformation.

- Heart rate increases, pumping blood to muscles and vital organs.

- Breathing accelerates, enhancing oxygen intake.

- Pupils dilate for better vision

- Muscles tense up, priming for action.

This is all part of the “fight or flight” response, automatically preparing you to either confront the threat or make an escape. (More on specific fight or flight behaviors in children below)

Brain Response:

Significant changes occur in your brain when the sympathetic nervous system is activated.

As the sympathetic nervous system floods the body with stress hormones like adrenaline and noradrenaline, the prefrontal cortex partially shuts down.

This part of the brain controls all your executive functions, including planning, decision-making, problem-solving, controlling impulses, logic, reasoning, and communication.

What does this mean?

- Your child will find it significantly more challenging to find the words to describe their thoughts, feelings, and what triggered them. They may even become nonverbal.

- Your child will not respond to logic, reasoning, or the potential consequences of their behavior if you try to communicate with them during this time.

It’s helpful to remember that if your child isn’t listening to you when they’re dysregulated, it isn’t a conscious choice they’re making to be difficult. It’s an automatic response happening in their brain.

The more immediate and severe the threat appears, the more significantly the prefrontal cortex will be impacted.

Resolution and Recovery:

20 to 60 minutes after the threat has passed, the body starts to normalize and recover from the fight-or-flight state. This is when the sympathetic nervous system’s counterpart, the parasympathetic nervous system, takes over.

Fight or Flight Behaviors in Children

We know the fight or flight response is an automatic response triggered in stressful situations by the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, but let’s look at what those behaviors look like so you can recognize when this is happening with your child.

“Fight or Flight” is a survival mechanism. However, in modern settings, these responses manifest as behaviors rather than literal fighting or fleeing.

Understanding these behaviors can help parents and caregivers respond more effectively to children’s needs during stressful moments.

Fight:

- Aggression: hitting, kicking, biting, or shouting

- Defiance: Refusing to comply with requests or instructions, arguing, and talking back

- Destructive Behavior: Breaking toys, throwing objects, or causing damage to their surroundings

Flight

- Avoidance: physically leaving the room, hiding, or engaging in activities that distract them from the stressor.

- Withdrawal: Social withdrawal or becoming unusually quiet, covering their face

- Rushing Through Tasks: Hurrying to finish tasks or skipping them altogether can also be a form of flight behavior, attempting to move past the source of stress quickly.

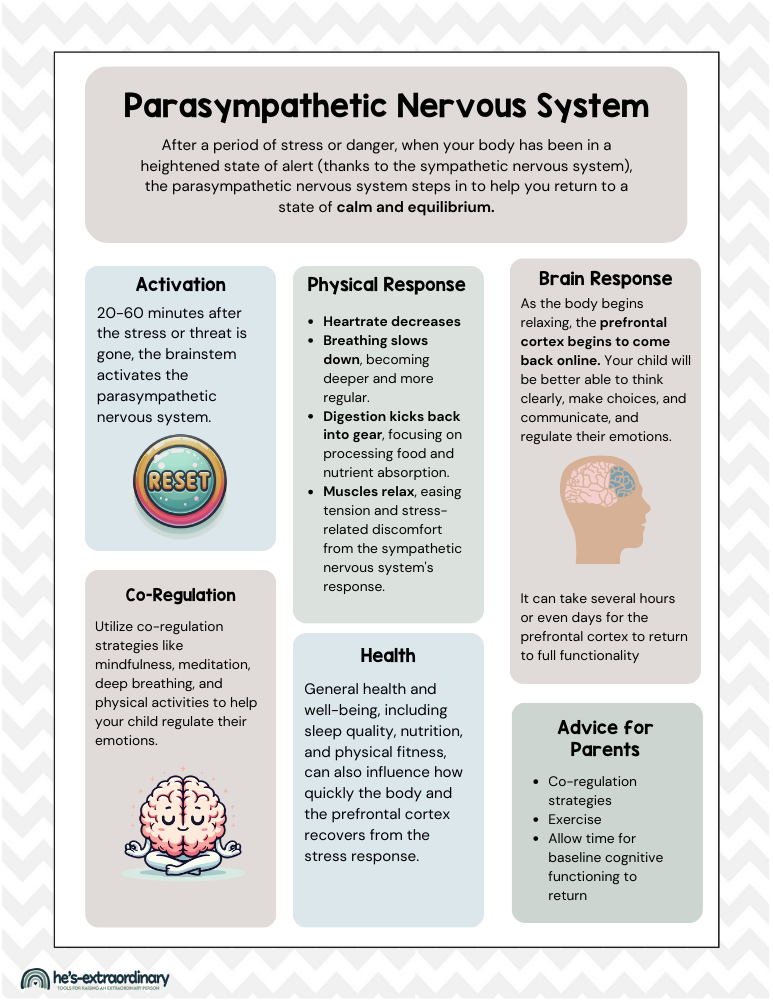

The Parasympathetic Nervous System

The opposite of the sympathetic nervous system, The parasympathetic nervous system acts as your body’s built-in relaxation response.

After a period of stress or danger, when your body has been in a heightened state of alert (thanks to the sympathetic nervous system), the parasympathetic nervous system steps in to help you return to a state of calm and equilibrium.

Here’s how the parasympathetic nervous system works:

Initiating Relaxation:

20-60 minutes after the stress or threat is gone, the brainstem activates the parasympathetic nervous system.

It’s like your child’s brain is now pressing a reset button, signaling their body that it’s safe to shift from high alert to peace mode.

Then, through a network of nerves, the parasympathetic nervous system sends out signals to the various organs and parts of the body. These signals tell them that the time for action has passed, and now it’s time to relax and recover.

Physical Response:

Once activated, several physiological changes occur:

- Heart rate decreases

- Breathing slows down, becoming deeper and more regular. This helps oxygenate the body thoroughly and enhances relaxation.

- Digestion kicks back into gear, focusing on processing food and nutrient absorption. Digestion slows down during stress.

- Muscles relax, easing tension and stress-related discomfort from the sympathetic nervous system’s response.

Reactivation of the Prefrontal Cortex

During the stress response, your child’s prefrontal cortex shuts down.

As the body begins relaxing, the prefrontal cortex begins to come back online. This reactivation is crucial. It means your child will be better able to think clearly, make choices, communicate, and regulate their emotions.

However, it’s important to understand that this process takes time, and the full function of their prefrontal cortex doesn’t happen as soon as the stress is gone.

How long does the prefrontal cortex’s full functionality take to return?

Typically, the prefrontal cortex starts regaining its functionality within a few minutes to hours after the stressor has been removed.

However, for it to return to full function, especially after prolonged or severe stress, it might take several hours or even days for some children.

The time it takes for the prefrontal cortex to return to full functionality varies widely depending on several factors:

- Intensity and Duration of the Stress: The more intense and prolonged the stress, the longer it may take for your child’s prefrontal cortex to recover fully. In situations of extreme or chronic stress, the recovery can be more gradual and may require more time.

- Individual Differences: People’s brains react differently to stress, and these individual differences can affect recovery times. Some kids may bounce back quickly, while others might need more time to return to their baseline cognitive functioning.

- Supportive Interventions: Children rely on adults to help them co-regulate their emotions in stressful situations. The level of positive support and intervention your child receives will impact how quickly their prefrontal cortex returns online. Practices such as mindfulness, meditation, deep breathing exercises, and physical activity can facilitate the return of prefrontal cortex functions by enhancing parasympathetic activity and reducing stress levels. Engaging in these practices with your child shortly after a stressful event can help speed up the recovery process.

- Overall Health and Well-being: General health and well-being, including sleep quality, nutrition, and physical fitness, can also influence how quickly the prefrontal cortex recovers. A healthier body often supports a more resilient and faster-recovering brain.

Additionally, repeated exposure to stress without adequate recovery can lead to longer-term impairments in the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, emphasizing the importance of stress management and co-regulation strategies to help your child recover and regulate their emotions.

It’s also worth noting that the body uses a ton of magnesium (a macronutrient) in the process of activating the parasympathetic nervous system. Approximately 72% of people are magnesium deficient, so you should explore whether or not a magnesium supplement could benefit your child.

The Enteric Nervous System (ENS)

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is often called the “second brain” of your body. It’s a huge network of nerves located in the walls of your gut, stretching from your esophagus down to your rectum.

Although it’s a component of the peripheral nervous system, it can operate independently. This means it can manage the digestive system all by itself without needing direct orders from your brain.

The brain and ENS are in constant communication with one another, and this impacts memory and emotional responses. This is why emotions like fear and anxiety are felt in our gut and why stress can induce gastrointestinal symptoms.

How the ENS Impacts Moods & Behavior

The enteric nervous system has a significant impact on mood and behavior, a relationship that’s often referred to as the “gut-brain axis.”

Here’s how the ENS plays a role in influencing mood and behavior:

- Production of Neurotransmitters: The ENS produces a wide range of neurotransmitters that play critical roles in regulating mood and emotions. For example, a large portion of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut. Serotonin promotes feelings of well-being and happiness.

- Communication with the Brain: The gut and the brain are constantly communicating with each other. When the environment in your gut changes (due to diet, stress, or other factors), the ENS sends signals to the brain that can impact mood and emotional state.

- Stress Response: The ENS is also involved in the body’s stress response. Stress can affect gut motility, secretion, and barrier function, and these changes in the gut can, in turn, send signals back to the brain that alter mood and behavior, often exacerbating feelings of stress or anxiety.

- Microbiome Interaction: The ENS interacts closely with the gut microbiome, the vast community of microorganisms living in the digestive tract. These microorganisms can produce and respond to neurotransmitters and other chemical messengers, influencing the ENS and, by extension, mood and behavior. Certain strains of gut bacteria have been found to have a direct effect on the production of neurotransmitters like serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which helps control feelings of fear and anxiety.

Important Takeaways for Parents:

As a parent, here are some key things to remember and take into account, especially if you’re raising a child who is neurodiverse and may spend more time with their stress response activated than their neurotypical peers.

1. Recognize the Signs of Overwhelm:

Understand that when a child is stressed, their sympathetic nervous system activates, preparing them for “fight or flight.” Recognizing the signs of this activation can help you respond appropriately.

Knowing your child’s early signs of stress is crucial for preventing meltdowns.

2. Patience During Dysregulation:

Remember, during moments of high stress, a child’s ability to process information, communicate, and respond logically is significantly reduced. Their prefrontal cortex, which controls these abilities, is not fully operational.

3. Wait for Calm:

Understand that it takes time for the parasympathetic nervous system to kick in and calm the body down after a stressor is gone. Attempting deep conversations or logical reasoning should wait until this system has had time to return the body to a state of calm.

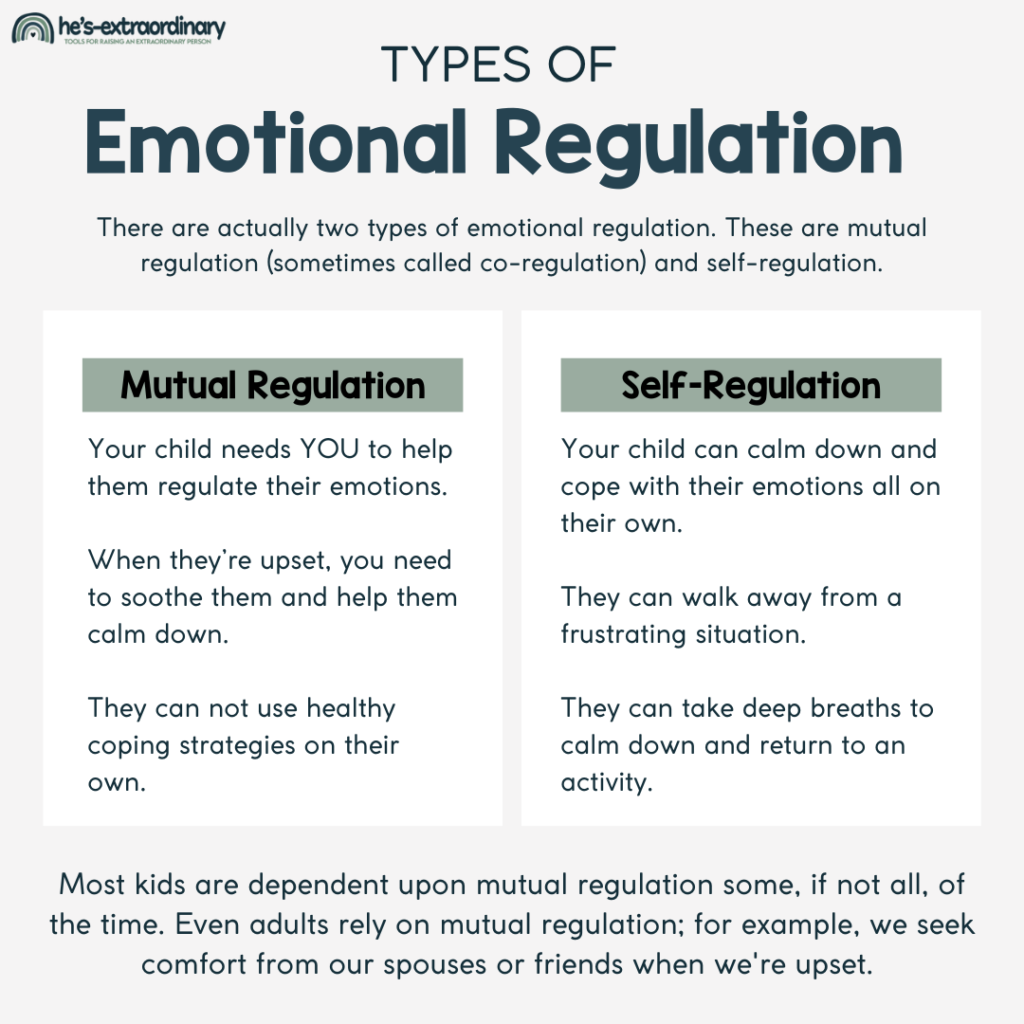

4. Co-Regulation

Know that the parasympathetic nervous system needs 20 to 60 minutes (or sometimes longer) to help the body recover from a high-stress state. Gentle, supportive interventions can facilitate this transition.

Utilize co-regulation strategies like mindfulness, meditation, deep breathing, and physical activities to help your child regulate their emotions. These activities not only support the parasympathetic nervous system but also enhance the re-engagement of the prefrontal cortex.

5. The Prefrontal Cortex Reactivates Gradually:

Just because your child’s body is calm doesn’t mean the full functionality of their prefrontal cortex is restored. It can take several hours or even days after the stress response before the prefrontal cortex fully returns online. Adjust expectations accordingly.

6. Healthy Gut, Healthy Mind:

Pay attention to your child’s gut health, recognizing its impact on mood and behavior through the enteric nervous system. Gastrointestinal symptoms are 3–4 times more common in children with ASD but are often overlooked.

A healthy diet, possibly enriched with probiotics, can support a positive mood and overall well-being.

7. Normalize the Experience:

Help your child understand that their reactions are a normal part of how their body responds to stress by teaching them about the fight-or-flight response.

This understanding can reduce shame and improve self-regulation over time.

8. Routine and Predictability:

For many children with autism, having a structured home environment helps them feel safe.

Generally, unexpected events, changes, or uncertainty may cause major stress for these children. This usually stems from not having a full understanding of how the world works.

Since this can trigger stress responses, maintaining a routine and predictability in your child’s environment can help minimize these triggers.

9. Health and Well-being:

Overall physical health, including regular exercise and adequate sleep, strengthens the nervous system’s resilience, potentially reducing the severity and duration of stress responses.

Using this information to guide parenting approaches can create a supportive environment that helps manage difficult moments more effectively and promotes a deeper understanding and connection between you and your child.

Sources:

- McCorry LK. Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007 Aug 15;71(4):78. doi: 10.5688/aj710478. PMID: 17786266; PMCID: PMC1959222.

- Fleming MA 2nd, Ehsan L, Moore SR, Levin DE. The Enteric Nervous System and Its Emerging Role as a Therapeutic Target. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020 Sep 8;2020:8024171. doi: 10.1155/2020/8024171. PMID: 32963521; PMCID: PMC7495222.

- Rao M, Gershon MD. The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Sep;13(9):517-28. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.107. Epub 2016 Jul 20. PMID: 27435372; PMCID: PMC5005185.