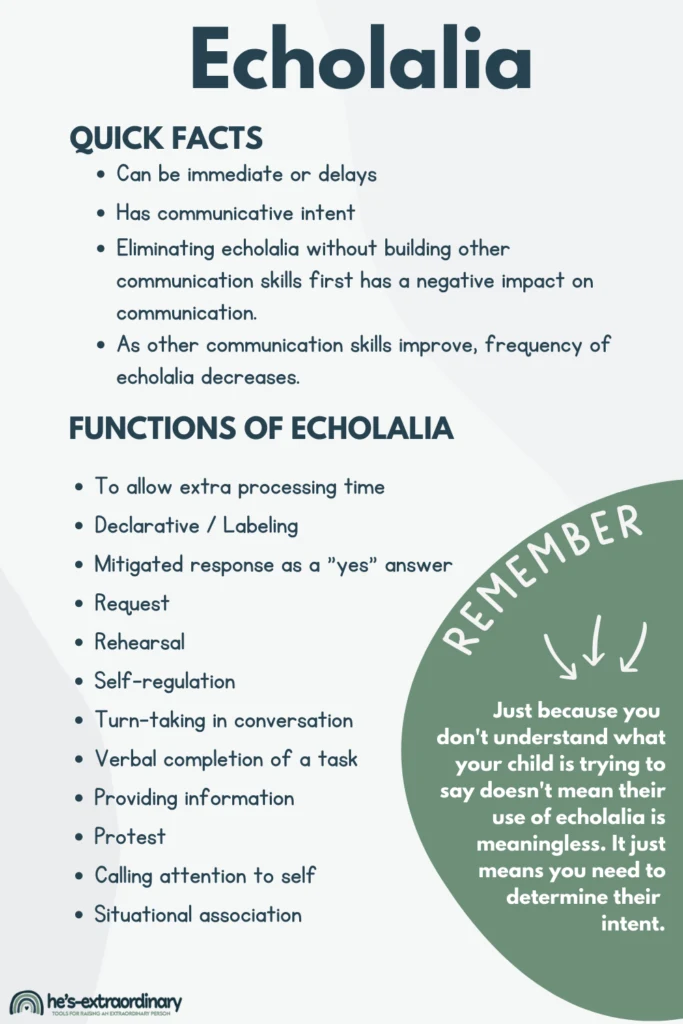

What’s inside this article: A description of echolalia, the types of echolalia, and an explanation of the possible functions (meanings) behind echolalia when used by children with autism.

A lot of people falsely believe that there are no functions of echolalia

It means if we can figure out what the child’s intentions are, then we may be able to understand them better.

This post is part of a 7 part series on techniques for improving communication skills. Each part of the series contains this table of contents so you can easily navigate to the other parts of the series.

Table of Contents

- Learning to Listen & Oral Language Comprehension

- Developing Oral Language Expression

- Developing Social Language and Conversation Skills

- Milestones of Play & Targeting Skills Through Play

- Augmentative and Alternative Communication Tools

- Childhood Development: Language and Communication Milestones

- The Functions of Echolalia

What is Echolalia?

First of all, echolalia is when an autistic individual repeats or echoes, words, sounds, or phrases that they have heard.

Echolalia can be immediate – occurring immediately after hearing the phrase, or delayed – happening later, and in different environments – it may happen many months or even years later (which means it can be extremely hard to determine if it’s echolalic or not).

Echolalia is actually a normal part of early childhood development and is expected of children during early language development.

However, sometimes with autistic children, their language development seems to stop there, or although more language develops, they still continue using echolalic phrases in certain circumstances.

Immediate Echolalia

Often, in ABA therapy, a therapist would try shaping echolalic speech. Basically, they would use the child’s echoic ability to get them to mimic the right response to a question.

For example, when a child echoes back questions, the therapist would shape the response by modeling the appropriate response and then reinforcing the use of the appropriate response when the child echoes it.

Basically, they focus on response training rather than spontaneous responses.

The problem with this ABA technique, however, is that the child is still echoing what was heard, and may later repeat the phrase to receive the reinforcer, but that doesn’t mean they comprehend what they’re saying.

The real answer to shaping immediate echolalia is simple, but the process of actually doing it is extremely complex.

You need to teach your child the expressive and receptive language comprehension skills so they can respond in a more functional way.

The aforementioned strategies in this series can be used in combination with one another to aid the development of communication

What Has Research Taught Us About Echolalia?

Typically, as communication develops, either through verbal language or AAC, echolalia diminishes. This is why I don’t recommend discouraging echolalia. Instead, it’s more beneficial to figure out the function it has for your child.

An article written by Barry Prizant and Judith Duchan entitled The Functions of Immediate Echolalia in Autistic Children (pp. 241-249) which appeared in the 1981 issue of the Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders is still the most comprehensive article on immediate echolalia.

Barry Prizant created the strength-based model of viewing autism and wholeheartedly believes in positive, person-centered interventions that teach new skills rather than reinforce a scripted answer.

In this article, he explained different possible functions of immediate echolalia and included clear examples of each.

When you understand that there are functions of echolalia, you can respond appropriately while modeling other communication strategies with the various teaching tools discussed in this series.

The following examples are directly from “The Functions of Immediate Echolalia in Autistic Children” by Barry M. Prizant.

Functions of Immediate Echolalia, Directed at Another Person

Turn-taking:

These are utterances used as turn-taking fillers during an alternating verbal exchange (conversation). It can also provide thinking and/or processing time for the person with ASD who has some verbal skills.

For an individual who lacks spontaneous verbal skills, echoing does allow participation in a back-and-forth interaction, even if it is

Since turn-taking is part of social communication, it does show they have an understanding of how social exchanges work and are able to engage in joint attention.

Example:

Adult speaker: “Where did you go Sunday?”

Echolalic speaker: He repeats, “Where did you go Sunday?” and then, gives a quick look to the adult.

Adult speaker: “Did you go to Grandma’s house?”

Echolalic speaker: Says, “Did you go to Grandma’s house?” then, he again gives a quick look at the speaker. Looking at the speaker is not an essential part of the sequence but it adds clarity to this text example.

The person with ASD who has some spontaneous verbal skills might eventually add, “No Grandma’s house; go

For this example, echolalia gave the individual extra processing time to understand and compose a spontaneous response to the speaker’s question.

Declarative

Utterances labeling objects, actions, or locations. Generally, these are accompanied by demonstrative gestures.

Example:

Adult speaker: As he checks the nearly empty cookie jar, he says, “I better buy some more cookies.”

Echolalic speaker: He also touches the cookie jar and says, “I better buy some cookies.” No verbal response or action is required from the adult speaker. However, the child does not attempt to take a cookie out of the jar.

For this example, the function of echolalia was to declare that he heard the speaker.

Yes Answer

Utterances used to request objects or others’ actions. Usually, this involves non-mitigated echolalia. (Non-mitigated responses are similar to yes answers/interactive examples cited in the next category.)

Example:

Adult speaker: “Do you want some juice?”

Echolalic speaker: “Do you want some juice?” then, he looks at the pitcher and continues to hold out his hand, waiting for a glass of juice.

In effect, he has indicated that he does want some juice. The function of the echolalia was to answer yes to the speaker’s question.

Request

Utterances are used to request objects or others’ actions.

Usually, this involves mitigated echolalia. Essentially, mitigated responses mean some changes are made to what was said.

(Non-mitigated responses are similar to yes answer/interactive examples cited in the previous category.) The examples of mitigation within the examples below are in bold for clarity.

Examples:

Example 1

Adult speaker:

“Do you want to watch TV?”

Echolalic speaker: “Yes, you want to watch TV, please.”

Example 2

Adult speaker:

“Can you give it to me?”

Echolalic speaker: “Yes, Jason can give it to me?”

Example 3

Adult speaker:

“Do you want some crackers?”

Echolalic speaker: “Do you want some pretzels?”

For each example, the echolalic speaker uses mitigated echolalia to request something or respond to a question.

Functions of Immediate Echolalia, Non-Interactive/Directed at Self

Non-focused

Utterances produced with no apparent interactive meaning or communicative intent; often spoken during states of high arousal (e.g., fear, frustration, pain).

But, these utterances do not appear to be an attempt at self-regulation.

Example

Adult speaker: “What’s wrong? Why are you screaming?”

Echolalic speaker: As he continues to walk and flap his hands, he intermittently screams and slaps his own face. Then, he begins to say to himself, “What’s wrong? Why are you screaming?”. As he continuously repeats, “What’s wrong? Why are you screaming?” he slaps his face again.

In this example, there is no clear function of the echolalia. However, you can’t be certain that there is no intent or association for the speaker.

Rehearsal

Utterances are used as a processing aid, followed by another utterance or action indicating comprehension of echoed utterance.

Adult speaker: “Give this to Jim.” (Hands over the notebook.)

Echolalic speaker: He turns around, starts pacing, then he softly says “Give this to Jim” several times. The pacing stops and he walks over to Jim. Then he gives the notebook to him.

In other words, it helps keep the demand in his working memory and his actions show he comprehends what was said.

Self-regulatory

Utterances serve as a means to regulate one’s own actions. Usually, these are p

Example:

Adult speaker: “Don’t jump on the bed.”

Echolalic speaker: He repeats “Don’t jump on the bed” several times to himself as he gradually decreases the jumping, ceases the action, and finally gets off the bed.

Using echolalia here both helped the speaker to regulate their actions and shift their mindset to follow the demand given by the adult.

As you can see, there are many possible functions of immediate echolalia. It can be hard for parents and teachers to determine what the child is trying to communicate – but echolalia is not “meaningless”.

Delayed Echolalia

Delayed echolalia is more difficult to decipher. A lot of times, there is no obvious meaning for the listener. This doesn’t mean the phrases have no meaning, however.

It means you may not have been present when the phrase was originally heard or may have forgotten since delayed echolalia can occur months or even years later.

When this is the case, it may be hard to determine if the speech is echolalic or spontaneous.

To understand the functions of delayed echolalia, it is helpful to think of it as a chunk of language that has been stored in memory but without regard to its literal meaning.

A situation or emotion can trigger the use of the speech, even if it seems to have no connection to the situation.

What I mean by this is, for example, if a child is feeling a certain emotion and hears a phrase from a TV commercial, then later (weeks, months) feels the same emotion, they may then repeat the phrase from the TV commercial.

So delayed echolalia can, in fact, be your child’s way of expressing their emotions.

What has Research Taught Us About Delayed Echolalia?

First, when delayed echolalic speech occurs, do not assume your child understands the content of the speech or that the phrase should be interpreted by its literal meaning.

Instead, try to determine the situation that elicited the speech and then prompt your child with appropriate language or visuals to use for the situation.

Unfortunately, there are times when families never figure out a logical connection or clear meaning for delayed echolalic utterances. In that case, it’s still important to provide your child with simple language or AAC tools they can use for the situation.

In 1984, Barry Prizant and Patrick Rydell published the “Analysis of Functions of Delayed Echolalia in Autistic Children “in the Journal of Speech and Hearing Research (Vol. 27, pp 183-192). Note: This is the companion article to the 1981 article on immediate echolalia noted above.

The functions of echolalia can be different from person to person. But the following examples from the Analysis of Functions of Delayed Echolalia in Autistic Children are some common meanings to help you decipher what your child may be telling you.

Functions of Delayed Echolalia, Directed at Another Person

Turn-taking

Utterances are used as turn fillers in an alternating verbal exchange.

Example:

Adult speaker: “What did you do this weekend?”

Echolalic speaker: “Don’t take your trunks off in the swimming pool.”

Adult speaker: “Oh, you went swimming?”

Echolalic speaker: “Put your goggles on. Then you won’t get chlorine in your eyes.”

The functions of echolalia are to take turns with a conversational partner and to offer information by repeating echolalic phrases from the event in question.

Verbal Completion

Utterances that complete familiar verbal routines initiated by others.

Example:

Adult speaker: “Wash your hands.”

Echolalic speaker: As he washes his hands, he says, “Good boy.” He said this because his teacher typically says the same phrase as a way of reinforcing completion of an act.

The function is to indicate that he is “all done” with a task. Establishing routines that reinforce daily task completion is important because it aids in transitions and independence.

Providing Information

Utterances offering new information not apparent from situational context (may be initiated or respondent).

Example

A parent is about to begin preparation for lunch. She says, “What would you like for lunch?” to her child.

Then her child begins singing a song about a brand name luncheon meat as a way of communicating that he would like a sandwich for lunch.

Prior, no luncheon meat was mentioned, nor was anything visible that would have triggered the idea of a specific luncheon meat sandwich.

The echolalia was used as a way of providing information to their parent.

Labeling

Utterances labeling objects or actions in the environment.

Example:

An adult and child are sorting through videotapes. Then the child picks up a Sesame Street video and begins singing a specific song as he makes a quick look at the adult.

The adult then acknowledges, “Yes, that’s one of your favorite songs from that tape.”

The child goes on looking through the pile; he doesn’t indicate that he had wanted to see the tape; thus, it was a comment of identification or recognition of the tape and a song associated with it.

The child was using delayed echolalia because it was a way for them to show the adult that they recognized the tape.

Protest

Utterances protesting the actions of others. For example, may be used to prohibit others’ actions and reflect prohibitions expressed by others.

Example

The

They are echoing what they’ve heard an adult say before to themselves or someone else when doing something that isn’t allowed.

Request

Utterances used to request objects.

Example:

The echolalic speaker goes to an adult and says, “Do you want juice?” as his means of asking for a drink or saying he’s thirsty.

In other words, the function of delayed echolalia is to make a request by repeating a phrase heard in the past to indicate what they want.

Calling

Utterances used to draw attention to oneself or to initiate an interaction.

Example:

A child named Jordan walks over to an adult, then says, “Jordan is an interesting name” as a means of initiating an interaction.

Directive

Utterances or imperatives used to direct another person’s actions

Example:

The echolalic speaker walks over to an adult standing by a DVD player and he says, “You. Ready; let’s exercise. Touch your toes, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8. Now to the left…”.

Using some dialogue from a videotape, he indicates that he wants the adult to play that video (an action) so he can exercise.

Functions of Delayed Echolalia, Non-Interactive (Direct at Self)

Situational Association

Utterances with no apparent communicative intent appear to be triggered by an object, person, situation, or activity.

Example:

The child sees the Indiana University logo in a store window and then begins to sing the Indiana fight song in Japanese. He has learned the song in Japanese from a commercial that aired during televised university basketball games.

Although no “apparent” function exists, that does not mean that echolalia is meaningless. The child shows that they have made an association between a previous memory and their current environment.

Rehearsal

Utterances produced with low volume followed by louder interactive production. Appears to be practiced for subsequent production.

Example:

The adult asks, “What do you want to eat?”

Echolalic child softly says to himself several times, “I want a cracker, please.” He then looks toward the adult and says, “I want a cracker, please,” at normal voice volume.

Label

Utterances labeling objects or actions in an environment with no apparent communicative intent. This may also be a form of practice for learning

Example:

The echolalic speaker notes an open window. Then he walks in big circles repeating, “Window. Close the window. It’s cold in here. (It’s 80 degrees outside.) Close the window.” He does not attempt to close it or get someone else to do it.

The speaker is simply using echolalic speech to communicate his observation. Therefore, the speech shouldn’t be interpreted literally.

Recap

Remember, echolalia is a normal part of speech development in toddlers. However, autistic individuals often continue to use echolalic speech through childhood and, at times, adulthood.

In the past, echolalia has been labeled as “meaningless speech” with no function or communicative intent. We now understand that echolalia has many possible functions, as described in the examples in this article.

Echolalia should not be discouraged. Generally, as communication skills improve, the occurrences of echolalic speech diminish.

The Best Tips to Improve Speech in Children With Autism ·

Tuesday 1st of October 2019

[…] The Functions of Echolalia […]

9 Strategies For Teaching Social Skills To ASD Children ·

Tuesday 1st of October 2019

[…] The Functions of Echolalia […]

PECS Visuals and AAC Technology for Autism - What You Need to Know

Monday 30th of September 2019

[…] The Functions of Echolalia […]

Childhood Development: Language and Communication Milestones

Monday 30th of September 2019

[…] The Functions of Echolalia […]

Sonakshi Rawal

Tuesday 20th of August 2019

Hi this is amazing. I'm an SLP and this just refreshed my knowledge.